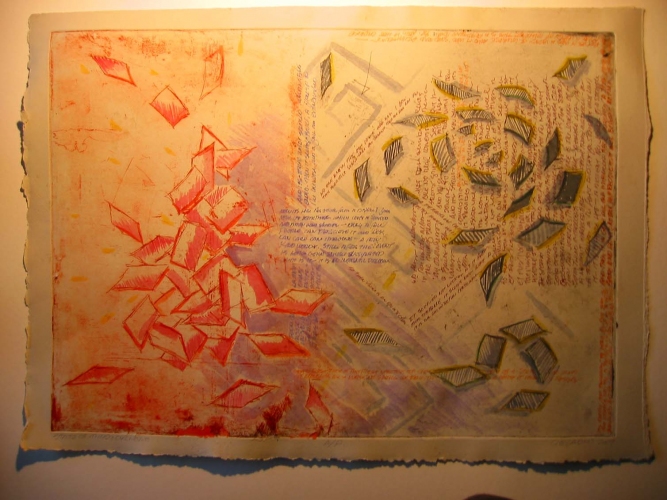

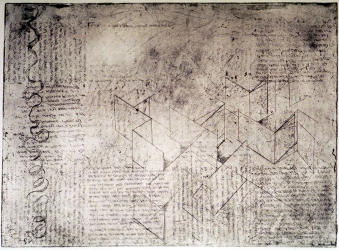

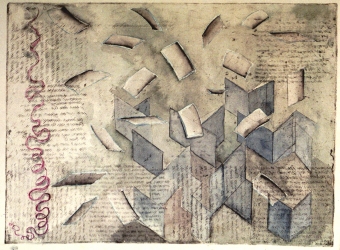

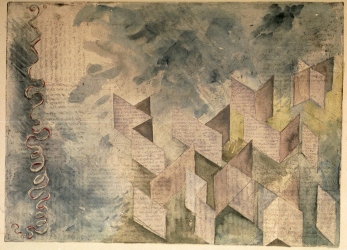

House of Cards

Palimpsest

2005

intaglio (state)

2005

intaglio (state)

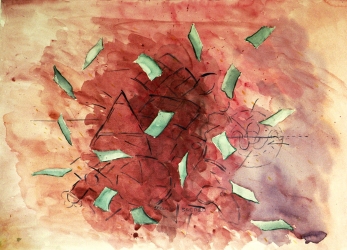

These watercolors and works on paper all depict a house of cards. I began drawing the house of cards as a figure of my psychological state during a period when my life felt so finely yet precipitously balanced that one little shock wave, wind, metaphorical storm, or even a figurative jiggle, could send everything crashing down. I was working at least two different jobs, taking care of my aged father, writing, keeping my visual art alive, and traveling across the vast cold lonely distances of the metropolitan area each day. This figure came into being after 9/11 when my daughter and her husband were working in Iraq. The images of explosions—of things blowing apart—filled my mind each morning and evening as I listened to the news.

The effects of the war and its associated catastrophes seem unreal. We cannot picture the specifics of a foreign city. We don’t consider the consequences these images will have on our psyches. But scenes of surprise, shock, and destruction linger in our consciousness and merge with everyday life. Even though we are far away from the mayhem of the war, and our own houses do not tumble down, the images reconfigure themselves in our unconscious and appear in other guises, as figures and emblems. So things blowing apart and tumbling down are universal figures for catastrophe—or, as Robert Burns said, “the best-laid plans,” which are always just about to go astray.

These distant events joined with other disasters in my imagination: car wrecks on First Avenue, coming home and finding my father sick or dead, losing my health insurance—very real possibilities in my life. And those are only the material possibilities; the metaphorical possibilities are endless. Entire civilizations could collapse.

Cards are figures of fortune. The act of carefully building and balancing the cards is inevitable, but always implicitly doomed. Dramatic irony governs the figure. We might all identify the house of cards with our own possibilities for disaster, or the precariousness of our lives.

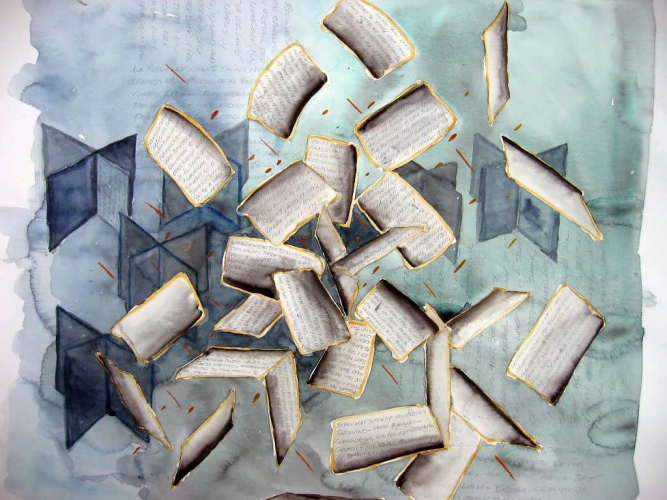

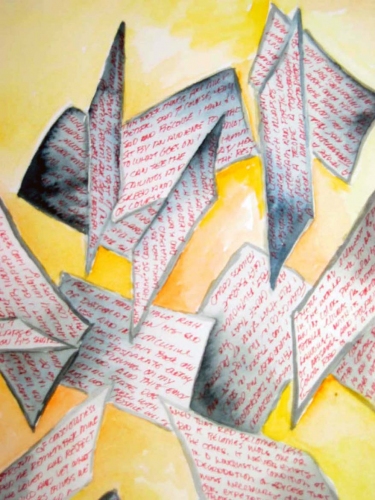

Some other figures work their way into these drawings: the labyrinth and the rooms or walls of words. The labyrinth is connected to puzzles and complications. It connotes the double consciousness of being both lost inside a situation and simultaneously above it, able to see your way out. The wall of words, and the sheets of paper, generally allude to my shifting feelings about my life in academia and my own writing. They allude to excess and imprisoning—the glossolalia connected with competitiveness, perhaps—both qualities of language. On the other hand, they likewise invoke the mysterious joy of letters and fictions.

In these days of computer-generated art, it is probably a curse to be able and even want to draw or paint. When I lift a brush or draw a figure in space, I am moving in exactly the opposite direction of the culture at large, and in some quite substantial ways: that’s the point.

Formally, there are the pleasures of frozen motion, of making a figure that seems real but resists mimesis, following an image through endless possibilities for variation. Returning to water color is like coming back to a favorite place, one which is filled with color.

Janina A. Ciezadlo, 2005

The effects of the war and its associated catastrophes seem unreal. We cannot picture the specifics of a foreign city. We don’t consider the consequences these images will have on our psyches. But scenes of surprise, shock, and destruction linger in our consciousness and merge with everyday life. Even though we are far away from the mayhem of the war, and our own houses do not tumble down, the images reconfigure themselves in our unconscious and appear in other guises, as figures and emblems. So things blowing apart and tumbling down are universal figures for catastrophe—or, as Robert Burns said, “the best-laid plans,” which are always just about to go astray.

These distant events joined with other disasters in my imagination: car wrecks on First Avenue, coming home and finding my father sick or dead, losing my health insurance—very real possibilities in my life. And those are only the material possibilities; the metaphorical possibilities are endless. Entire civilizations could collapse.

Cards are figures of fortune. The act of carefully building and balancing the cards is inevitable, but always implicitly doomed. Dramatic irony governs the figure. We might all identify the house of cards with our own possibilities for disaster, or the precariousness of our lives.

Some other figures work their way into these drawings: the labyrinth and the rooms or walls of words. The labyrinth is connected to puzzles and complications. It connotes the double consciousness of being both lost inside a situation and simultaneously above it, able to see your way out. The wall of words, and the sheets of paper, generally allude to my shifting feelings about my life in academia and my own writing. They allude to excess and imprisoning—the glossolalia connected with competitiveness, perhaps—both qualities of language. On the other hand, they likewise invoke the mysterious joy of letters and fictions.

In these days of computer-generated art, it is probably a curse to be able and even want to draw or paint. When I lift a brush or draw a figure in space, I am moving in exactly the opposite direction of the culture at large, and in some quite substantial ways: that’s the point.

Formally, there are the pleasures of frozen motion, of making a figure that seems real but resists mimesis, following an image through endless possibilities for variation. Returning to water color is like coming back to a favorite place, one which is filled with color.

Janina A. Ciezadlo, 2005