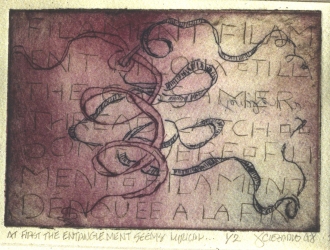

The History of the Knot

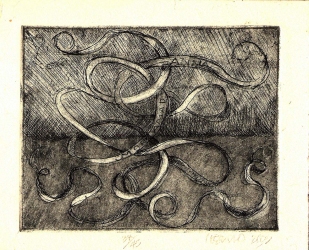

blue knot

2001

paper transfer lithography

8"x10"

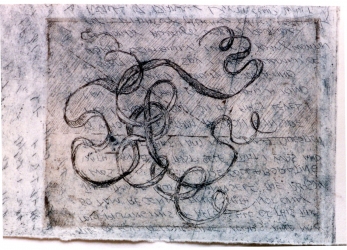

2001

paper transfer lithography

8"x10"

Some Notes on the History of the Knot

The technique I have used to produce this suite of prints is called dry-point engraving. The lines which form the images are engraved, or drawn, using a fair amount of pressure, into sheets of lexan. Lexan is a durable plastic material used for the windows of NASCAR racers and bullet-proof windshields. Dry-point on copper is a venerable technique usually associated with a certain spontaneity and improvisatory quality (although people who ride busses will recognize the process: a close variant is used to “tag” the windows.) As in watercolor, mistakes in engraving can’t be easily corrected, so gesture, the qualities of hand and fortuitous mistakes are important. Because the line is engraved rather than etched, it tends to be rather coarse. A true engraving is executed with a series of burins which produce lines by slicing through the metal with a V-shaped instrument rather than a point dragged across the surface. Whistler, among the great 19th century printmakers was known for his dry-points. One of the prints in this exhibition (Found Marks) is simply two practice plates-random marks made by several high school students trying out the dry-point needle—then printed together in color. Excellent proof, I think , of the tenets of Dada and Abstract Expressionism.

After the image is engraved on the plate, it is inked. Ink is rolled on with a brayer and wiped with a stiff net-like material called a tarlatan. The ink is wiped off the surface and stays in the engraved lines. The ink film that remains is called: “plate tone.” Finally , the plate is placed face up on the press and covered with a piece of cotton or rag paper (paper made from cotton rags so it has no acid from wood pulp which will turn it yellow over time) and run through an etching press. An impression is made by the ink which is forced out of the lines onto the paper. Color images are produced by using two or more different plates. This general method of reproducing visual images began with woodcuts in the Middle Ages (and the engraving used to decorate a knight’s armor) and held sway as the only method for reproducing visual images until lithography and then photography came into practice during the 19th century. After its commercial viability became problematic the process was relegated eclusively to the fine arts.

It is common to produce prints in a series, folio or suite. The numbers and letters refer to the number of prints made from a plate in an edition. So 5/10 would mean that there are 10 impressions in an edition (a limited and controlled group of prints) and you are looking at the fifth one. After an edition is printed, it is customary to strike the plate—gouging a line through it, insuring that no extra prints are pulled, thereby increasing the value of the edition. A/P means that the print is an artist’s proof or a working proof pulled by the artist and master printer (in this case, both residing in myself) to determine exactly what the print will look like. There is a fair amount of variation in inking, color, choice of paper and other aspects of the process, so the artist and printer make proofs of a print until they decide what it should look like. Once the appearance of the print settled on, all prints in an edition will ideally be identical. Histoire du Noued was printed at a professional atelier (print workshop) named Anchor Graphics on Hubbard Street (sic) in Chicago.

The cover of HUBBUB ( a poetry journal published by Lisa Steinman And Jim Shugrue) was produced by off-set lithography. A photograph is made of the image, reduced to half-tones and transferred to an aluminum plate, a more mechanized and predictable method of mass production of visual images which superceded stone lithography in the early twentieth century.

The History of the Knot is an indefinite narrative which contains some word-play and a lot of associative thinking. There are many, many idioms which use the image of a knot to denote complexity, difficulty, complication and connection. We speak of a knotty problem, or being tied-up in knots. A knot is an incredibly complex figure to describe mathematically-or so I am told. I have linked my images of knots with other aspects of thread and string such as the coils which appear in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, which certainly seemed knot-like. In any case we speak of tying and untying the knot, cutting the cord and getting all tangled up. The Bible tells us that we are “knitted (comes from knot) into our mother’s wombs.” The term networks has come into common parlance although none of us present would use it as a verb, but the noun node is related etymologically to noeud.

The literary use of the term with which all teachers of English are familiar is dénouement or “untying of the knot” at the end of novel. A filou is a thief in French (the spelling filoux comes from the 17th century poem about Paris) and refers directly to the cutting of purse strings. Both men and women carried purses. The word filon means string. Hearts, like purses have strings and can be stolen. And Whitman speaks of filaments (at First the Entanglement..) Swinburne speaks of a golden net and silver string.” As we all know, the fates (Clotho—hence cloth) stand poised with their scissors over the fabric of our lives.

Among the purely visual references is a diagram of the knot work in gold which was found in Sutton Hoo—Beowolf’s treasure trove—which appears in the Nature of Knot. I used my father’s Merchant Marine Handbook and my Encyclopedia of Needlework for some preliminary studies as well centuries of ornamental line-work used by engravers. (from wall text from a 1998 exhibition at Wright College, The City Colleges of Chicago)

Later studies produced through stone and paper lithography, intaglio continue to explore the original visual and verbal ideas)

The technique I have used to produce this suite of prints is called dry-point engraving. The lines which form the images are engraved, or drawn, using a fair amount of pressure, into sheets of lexan. Lexan is a durable plastic material used for the windows of NASCAR racers and bullet-proof windshields. Dry-point on copper is a venerable technique usually associated with a certain spontaneity and improvisatory quality (although people who ride busses will recognize the process: a close variant is used to “tag” the windows.) As in watercolor, mistakes in engraving can’t be easily corrected, so gesture, the qualities of hand and fortuitous mistakes are important. Because the line is engraved rather than etched, it tends to be rather coarse. A true engraving is executed with a series of burins which produce lines by slicing through the metal with a V-shaped instrument rather than a point dragged across the surface. Whistler, among the great 19th century printmakers was known for his dry-points. One of the prints in this exhibition (Found Marks) is simply two practice plates-random marks made by several high school students trying out the dry-point needle—then printed together in color. Excellent proof, I think , of the tenets of Dada and Abstract Expressionism.

After the image is engraved on the plate, it is inked. Ink is rolled on with a brayer and wiped with a stiff net-like material called a tarlatan. The ink is wiped off the surface and stays in the engraved lines. The ink film that remains is called: “plate tone.” Finally , the plate is placed face up on the press and covered with a piece of cotton or rag paper (paper made from cotton rags so it has no acid from wood pulp which will turn it yellow over time) and run through an etching press. An impression is made by the ink which is forced out of the lines onto the paper. Color images are produced by using two or more different plates. This general method of reproducing visual images began with woodcuts in the Middle Ages (and the engraving used to decorate a knight’s armor) and held sway as the only method for reproducing visual images until lithography and then photography came into practice during the 19th century. After its commercial viability became problematic the process was relegated eclusively to the fine arts.

It is common to produce prints in a series, folio or suite. The numbers and letters refer to the number of prints made from a plate in an edition. So 5/10 would mean that there are 10 impressions in an edition (a limited and controlled group of prints) and you are looking at the fifth one. After an edition is printed, it is customary to strike the plate—gouging a line through it, insuring that no extra prints are pulled, thereby increasing the value of the edition. A/P means that the print is an artist’s proof or a working proof pulled by the artist and master printer (in this case, both residing in myself) to determine exactly what the print will look like. There is a fair amount of variation in inking, color, choice of paper and other aspects of the process, so the artist and printer make proofs of a print until they decide what it should look like. Once the appearance of the print settled on, all prints in an edition will ideally be identical. Histoire du Noued was printed at a professional atelier (print workshop) named Anchor Graphics on Hubbard Street (sic) in Chicago.

The cover of HUBBUB ( a poetry journal published by Lisa Steinman And Jim Shugrue) was produced by off-set lithography. A photograph is made of the image, reduced to half-tones and transferred to an aluminum plate, a more mechanized and predictable method of mass production of visual images which superceded stone lithography in the early twentieth century.

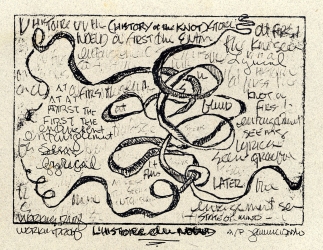

The History of the Knot is an indefinite narrative which contains some word-play and a lot of associative thinking. There are many, many idioms which use the image of a knot to denote complexity, difficulty, complication and connection. We speak of a knotty problem, or being tied-up in knots. A knot is an incredibly complex figure to describe mathematically-or so I am told. I have linked my images of knots with other aspects of thread and string such as the coils which appear in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, which certainly seemed knot-like. In any case we speak of tying and untying the knot, cutting the cord and getting all tangled up. The Bible tells us that we are “knitted (comes from knot) into our mother’s wombs.” The term networks has come into common parlance although none of us present would use it as a verb, but the noun node is related etymologically to noeud.

The literary use of the term with which all teachers of English are familiar is dénouement or “untying of the knot” at the end of novel. A filou is a thief in French (the spelling filoux comes from the 17th century poem about Paris) and refers directly to the cutting of purse strings. Both men and women carried purses. The word filon means string. Hearts, like purses have strings and can be stolen. And Whitman speaks of filaments (at First the Entanglement..) Swinburne speaks of a golden net and silver string.” As we all know, the fates (Clotho—hence cloth) stand poised with their scissors over the fabric of our lives.

Among the purely visual references is a diagram of the knot work in gold which was found in Sutton Hoo—Beowolf’s treasure trove—which appears in the Nature of Knot. I used my father’s Merchant Marine Handbook and my Encyclopedia of Needlework for some preliminary studies as well centuries of ornamental line-work used by engravers. (from wall text from a 1998 exhibition at Wright College, The City Colleges of Chicago)

Later studies produced through stone and paper lithography, intaglio continue to explore the original visual and verbal ideas)

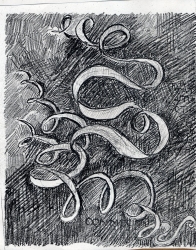

histoire du noued

1998

drawing

5"x7"

1998

drawing

5"x7"

Some Notes on the History of

The History of the Knot is an indefinite narrative which contains some word-play and a lot of associative thinking. There are many, many idioms which use the image of a knot to denote complexity, difficulty, complication and connection. We speak of a knotty problem, or being tied-up in knots. A knot is an incredibly complex figure to describe mathematically-or so I am told. I have linked my images of knots with other aspects of thread and string such as the coils which appear in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, which certainly seemed knot-like. In any case we speak of tying and untying the knot, cutting the cord and getting all tangled up. The Bible tells us that we are “knitted (comes from knot) into our mother’s wombs.” The term networks has come into common parlance although none of us present would use it as a verb, but the noun node is related etymologically to noeud.

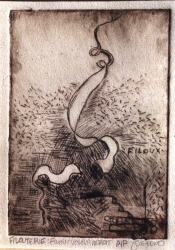

The literary use of the term with which all teachers of English are familiar is dénouement or “untying of the knot” at the end of novel. A filou is a thief in French (the spelling filoux comes from the 17th century poem about Paris) and refers directly to the cutting of purse strings. Both men and women carried purses. The word filon means string. Hearts, like purses have strings and can be stolen. And Whitman speaks of filaments (at First the Entanglement..) Swinburne speaks of a golden net and silver string.” As we all know, the fates (Clotho—hence cloth) stand poised with their scissors over the fabric of our lives.

Among the purely visual references is a diagram of the knot work in gold which was found in Sutton Hoo—Beowolf’s treasure trove—which appears in the Nature of Knot. I used my father’s Merchant Marine Handbook and my Encyclopedia of Needlework for some preliminary studies as well centuries of ornamental line-work used by engravers. (from wall text from a 1998 exhibition at Wright College, The City Colleges of Chicago)

Later studies produced through stone and paper lithography, intaglio continue to explore the original visual and verbal ideas)

The History of the Knot is an indefinite narrative which contains some word-play and a lot of associative thinking. There are many, many idioms which use the image of a knot to denote complexity, difficulty, complication and connection. We speak of a knotty problem, or being tied-up in knots. A knot is an incredibly complex figure to describe mathematically-or so I am told. I have linked my images of knots with other aspects of thread and string such as the coils which appear in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, which certainly seemed knot-like. In any case we speak of tying and untying the knot, cutting the cord and getting all tangled up. The Bible tells us that we are “knitted (comes from knot) into our mother’s wombs.” The term networks has come into common parlance although none of us present would use it as a verb, but the noun node is related etymologically to noeud.

The literary use of the term with which all teachers of English are familiar is dénouement or “untying of the knot” at the end of novel. A filou is a thief in French (the spelling filoux comes from the 17th century poem about Paris) and refers directly to the cutting of purse strings. Both men and women carried purses. The word filon means string. Hearts, like purses have strings and can be stolen. And Whitman speaks of filaments (at First the Entanglement..) Swinburne speaks of a golden net and silver string.” As we all know, the fates (Clotho—hence cloth) stand poised with their scissors over the fabric of our lives.

Among the purely visual references is a diagram of the knot work in gold which was found in Sutton Hoo—Beowolf’s treasure trove—which appears in the Nature of Knot. I used my father’s Merchant Marine Handbook and my Encyclopedia of Needlework for some preliminary studies as well centuries of ornamental line-work used by engravers. (from wall text from a 1998 exhibition at Wright College, The City Colleges of Chicago)

Later studies produced through stone and paper lithography, intaglio continue to explore the original visual and verbal ideas)