Recent Writing

Published Reviews

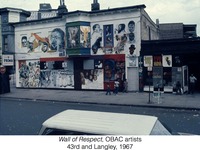

Walls of Prophecy and Protest: William Walker and the Roots of a Revolutionalry Public Art Movement By Jeff W. Huebner

Book Review posted: 4/5/20

The New Art Examiner

http://www.newartexaminer.org/walls-of-prophecy.html

Book Review posted: 4/5/20

The New Art Examiner

http://www.newartexaminer.org/walls-of-prophecy.html

Thoughts in and on Quarantine

March 2020

AICA (Association International Critiques des Artes, USA Division)

March 2020

AICA (Association International Critiques des Artes, USA Division)

Art Critics on Emergency is a real-time collective diary by AICA-USA members about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on art critics, artists, arts institutions, art education, and the arts at large. AICA-USA members are invited to submit journalistic reflections and critical observations about this moment as it unfolds.

American Factory Reichert and Bognar

Hyperallergic August 20, 2019

Hyperallergic August 20, 2019

https://hyperallergic.com/513923/american-factory-documentary-netflix/

The Essay Film in Time and Space: An Interview with Mark Cousins

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Studies

Vol.46 #1

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Studies

Vol.46 #1

The historic first part-time faculty union in the nation at Columbia College held the two-day strike to convey to the administration the seriousness of unresolved bargaining issues.

Read Here: https://hyperallergic.com/414986/strike-at-columbia-college-chicago-spotlights-problems-for-part-time-faculty/?utm_source=email&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=sw

Hyperallergic December 2017

Read Here: https://hyperallergic.com/414986/strike-at-columbia-college-chicago-spotlights-problems-for-part-time-faculty/?utm_source=email&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=sw

Hyperallergic December 2017

The Seasons In Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

March/April 2017 vol. 44 no. 5

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

March/April 2017 vol. 44 no. 5

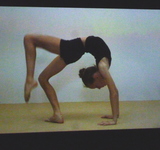

Rineke Dijkstra: Rehearsals

Milwaukee Art Museum Fall 2016

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

V.44, No. 4

Milwaukee Art Museum Fall 2016

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

V.44, No. 4

Book Review: The Volatile Smile

Afterimage: The Journal Of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

November/December 2015 Vol.43 No.3

Afterimage: The Journal Of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

November/December 2015 Vol.43 No.3

By Beate Geissler, Oliver Sann, Brian Holmes

Verlag fur moderne Kunst

NÜRNBURG

2014/179 pp.

Verlag fur moderne Kunst

NÜRNBURG

2014/179 pp.

Sarah And Joseph Belknap at the MCA

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

v.42 no.6 May/June 2015

photo: Janina Ciezadlo

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

v.42 no.6 May/June 2015

photo: Janina Ciezadlo

Report: Unsuspending Disbelief: The Subject of Pictures

Symposium at the Grey Center Lab, Midway Studios

The University of Chicago November 2014

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism Vol. 42 No. 4

Symposium at the Grey Center Lab, Midway Studios

The University of Chicago November 2014

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism Vol. 42 No. 4

photo: Thomas Struth: Janina Ciezadlo

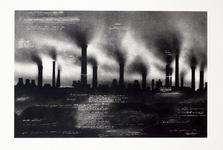

The Way of the Shovel: MCA January 2014

Afterimage the Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism Vol. 41 No.2

Image: Tacita Dean. The Russian Ending

Afterimage the Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism Vol. 41 No.2

Image: Tacita Dean. The Russian Ending

It's The Economy, Stupid at Gallery 400

Newcity November 2013

Newcity November 2013

http://art.newcity.com/2013/11/19/review-its-the-political-economy-stupidgallery-400/#more-15119

Or click on image

Or click on image

Marketing and Dreaming: Two Films about the Future of Europe

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

September/October Vol.41 NO.2

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

September/October Vol.41 NO.2

People of the North Portal

Barbara Crane

Generative Dynamics 2009

Barbara Crane

Generative Dynamics 2009

I have added this review because the site where it could be found Bauhaus 90/90 no longer exists.

R.H. Quaytman: Passing Through the Opposite of What it Approaches, Chapter 25

The Renaissance Society January 2013

Newcity Art January 2013

The Renaissance Society January 2013

Newcity Art January 2013

"Planning and Maintaining a Perrenial Garden III," Faheem Majeed

Chicago Cultural Center

Newcity Art 2013

Chicago Cultural Center

Newcity Art 2013

De-Natured: German Art from Joseph Beuys to Martin Kippenberger

Block Museum, Northwestern University

Newcity 10.09.12

Block Museum, Northwestern University

Newcity 10.09.12

Black Night Falling: Black holes and Constellations Kerry James Marshall at Monique Meloche

Newcity Arts March 2012

Newcity Arts March 2012

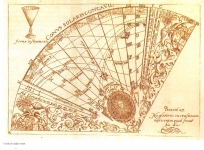

Prints and The Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe

The Block Museum of Art

NewCity February 2012

The Block Museum of Art

NewCity February 2012

Profile of the Artist: Molly Zuckerman-Hartung

NewCity Art February 2012

Negative Joy at Corbett vs. Dempsey

NewCity Art February 2012

Negative Joy at Corbett vs. Dempsey

The Wroclaw School of Printmaking: Faculty of the Eugeniusz Geppert Academy of Fine Art and Design

Chicago Cultural Center

NewCIty Art January 2012

Chicago Cultural Center

NewCIty Art January 2012

Image: What is Going On in Zeglarska Street?

Jacek Szewczyk

Jacek Szewczyk

Eye Exam: Joan Mitchell's Life and Art

Joan Mitchell, Lady Painter Patricia Albers

NewCity November 22

Joan Mitchell, Lady Painter Patricia Albers

NewCity November 22

Lewis Baltz: Producing Anonymity

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

vol.38 no.4

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

vol.38 no.4

Profile of the Artist: Phillip Hanson

New City September 2010

The Subtle Diagram (When in Disgrace...)

New City September 2010

The Subtle Diagram (When in Disgrace...)

Light Revisited:Elements of Photography at the MCA

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism v.37, no.3 2009

International Arts Journalism Institute for the Visual Arts

June 2009

American University, Washington DC

June 2009

American University, Washington DC

Writings are from the IAJIVA

Blog.

Blog.

The Collaborative Vision: Image Influenceing Words and Words Influencing Images

Chicago Artist's New

April 2009

Chicago Artist's New

April 2009

From The Monthly Scan

January 2009

January 2009

Review of Protect, Protect, Jenny Holzer at the Museum of Contemporary Art

Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism

History and Memory

Vol. 33 No. 4

History and Memory

Vol. 33 No. 4

Burnt Oranges

by Silvia Malagrino

2005

by Silvia Malagrino

2005

Major and Minor:Media Coverage of the Arts in Chicago and Beyond

Chicago Artist's Coalition News

June 2007 and July/August 2007

Volume XXXIV #6 and #7

June 2007 and July/August 2007

Volume XXXIV #6 and #7

Surrealism Here and Now

From Artscope 2002

From Artscope 2002

Image: Return to Cibola by Franklin Rosemont, Penelope Rosemont and Ody Saban 2002